The following was originally published in 1999

The Rationalist Press Association was founded in 1899, the same year that Robert Ingersoll, the America's leading agnostic of the nineteenth century, died. Both shared the same commitment to rationalism. This rationalism spoke to the interests and needs of the nineteenth century, and it may seem a bit quaint today. The publishing program of the Rationalist Association made a major contribution in its day, and we look back to this with gratitude. The founding statement of the RPA[^'Rationalism may be defined as the mental attitude which unreservedly accepts the supremacy of reason and aims at establishing a system of philosophy and ethics, verifiable by experience and independent of all arbitrary assumptions of authority.'] is still attractive to us today-though we need to elaborate on it, for example, by emphasizing the role that scientific methods of inquiry provide in testing claims to truth, and also seeking to apply science to concrete moral, political and social problems. The broad rationalist, secular, scientific agenda nonetheless has made many strides in the last century and on many fronts: Science and scientific methods continue to make impressive gains and to be applied to wider areas of human interest. The right of dissent, including atheism, is now widely accepted, at least in the democratic countries of the world (the problem that Bradlaugh faced is very rarely encountered today). The educational institutions, schools, universities, and colleges in most democratic countries are permeated with secular concerns and interests. And there are great libraries, museums, magazines, and books devoted to furthering science and reason.

Unfortunately, at the same time, there are many minuses. Notably, there has been a growth of fundamentalist and orthodox religions throughout the world--they have not declined as confidently predicted in 1899. Similarly, the 20th century has seen the rise and defeat of irrational totalitarian ideologies, such as fascism and communism. And in recent decades there has been a growth of new cults of unreason and the paranormal, fanned by irresponsible media. Postmodernism has also emerged to challenge the rationalist outlook.

The greatest failure is, of course, that the double standard still persists today as in 1899. Many highly educated persons (including scientists) will apply rationalism to their own fields, but will nonetheless continue to defer to religious faith. Criticism of religion is considered, in many backwater countries (such as the United States), if not dangerous, at least in bad taste.

In 1999 we can ask, What is to be done in the future? I wish to briefly suggest three necessary additions to the rationalist agenda:

First, rationalism needs to go beyond an intellectual statement or a limited publishing programme, and to be supplemented by humanism. This has already occurred with the founding of the British Humanist Association and other humanist organizations worldwide. It is recognized that we need to translate rationalism into praxis and go beyond being a debating society. It is the relevance of rational humanism to a person's eupraxsophy or life stance that is vital, including its relevance to concrete moral, social, and political issues.

Second, we need to create 'new institutions'. Here I think that both the rationalists and humanists have been remiss. As a starting point, I would recommend that we need to create our own secular humanist nursery, primary, secondary schools and develop new curricula programs for colleges and universities, in which the rationalist outlook and humanist values are explicitly represented. Thus we need to take rationalism/humanism to children, adolescents, and young people. But we need to satisfy the needs of people of all ages, including singles, families, and retirees. The recent effort in the humanist movement, for example, to provide celebrations and ceremonies to mark the rites of passage is an important step in this direction. But I would go further. I submit that we need to develop new community 'Centers for Inquiry and Human Enrichment'. These Centers will satisfy our intellectual interests, they will also address emotional needs and provide friendship centers for replenishment and renewal, and they will serve as an alternative to the established churches in our midst. They will be a place where meaningful humanist life stances can be cultivated as an alternative to an alienated life in the banal, consumer-oriented, media-driven societies in which so many isolated individuals now live.

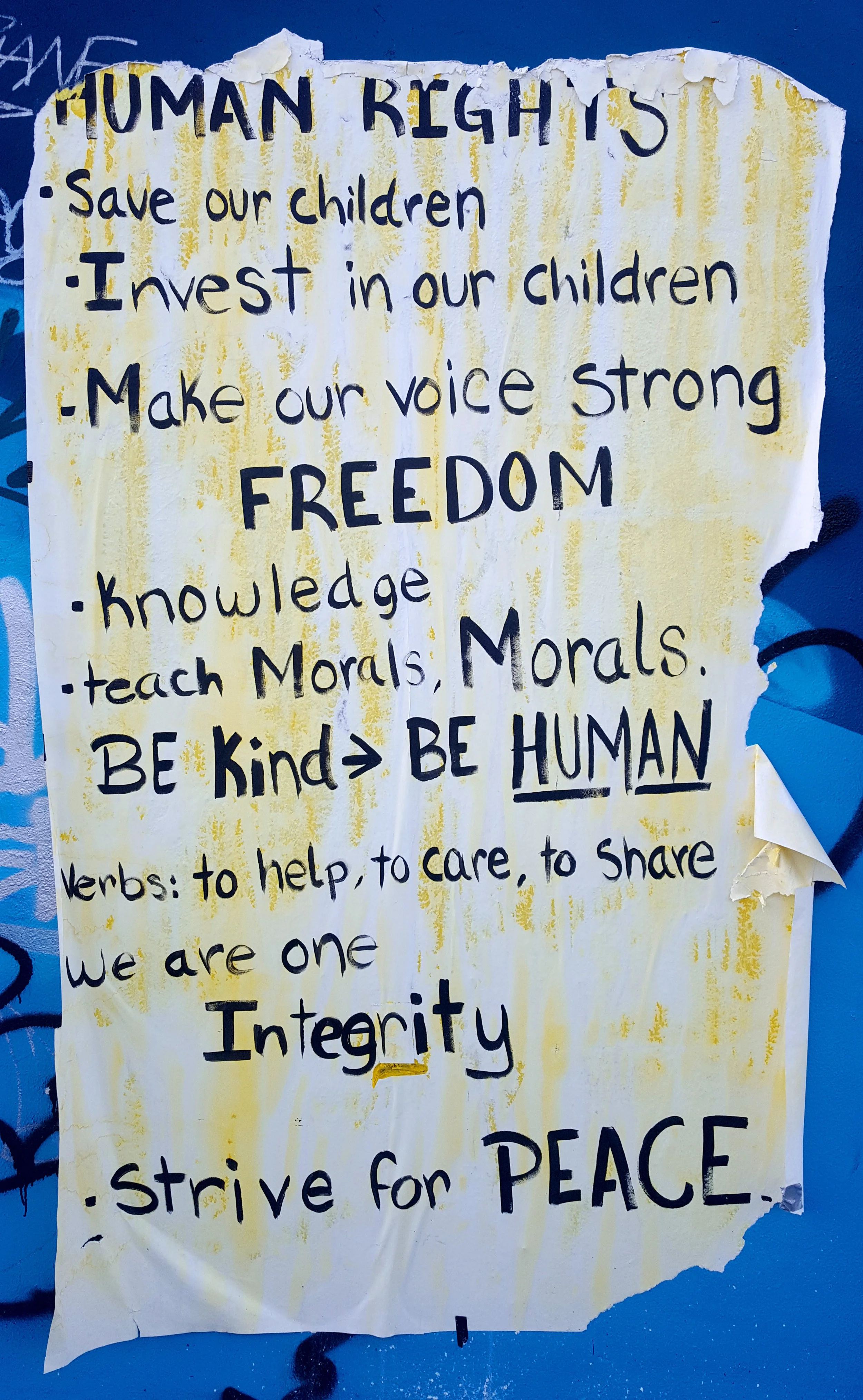

Third, we need to forge a new humanist worldwide coalition to defend the ideas and values of humanism and to respond to the assaults on human rights and freedom of conscience and action.